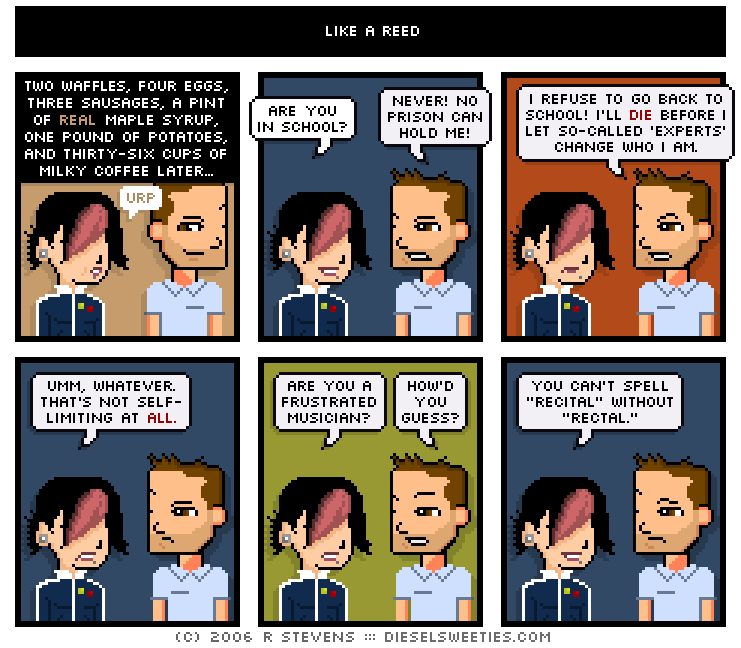

and then...she found happiness.

[happiness is specifically in words "are you in school?" "never! no prison can hold me!" "I refuse to go back to school! I'll die before I let so-called 'experts' change who I am"]

After a few days of facing reality, I've realized how freakin' scared i am. (so scared that i've hardly left my bed).

i've been in school straight from pre-kindergarten to law school. as i told one of my friends recently, i never thought this is where i would hve been at age 24. Nope, i'm sure if you asked me at my high school graduation where i would be at age 24, i'd have answered somewhere awesome. i'd be touring with some fantastic band or writing my second novel (after the wonderful feedback from my first novel).

but nope, at age 24, i have a law degree (which i really didn't want); i'm in pittsburgh (which i really don't like); and i'm just generally unhappy.

UNTIL...

2) Erik's blog told me about "Webcast Berkeley" - and i regretted not getting a degree from there - why bother now? (just kidding - i'm sure it would be fantastic). Currently, i'm listening to Art 23. The site/syllabus.

Foundations of American Cyber-Cultures

How do new media reinforce pre-existing social hierarchies and also offer possibilities for the transcendence of those very categories? Our course offers students an opportunity to think critically about, and engage in creative experiments in, the complex interactions between new media and perceptions and performances of embodiment, agency, citizenship, collective action, individual identity, time and spatiality. We pay particular attention to the categories of personhood that make up the UC Berkeley American Cultures requirements of race and ethnicity, as well as to gender, nationality, and disability.

New media--media which are defined through programs and structures rather than content--can be yet another means for dividing and disenfranchising and can be the conduit of violence and transnational dominance. At the same time, new media have already begun to offer exciting creative, subversive, informational and organizational forms that liberate in beautiful and unexpected ways. We aim to explore both these strands as well as the surprising links between them.

Taught by a practitioner of creative media exploration and critical technical practice, the course capitalizes on the rapid deployment potential of new media, especially online media. Rapid deployment of new media content allows students to engage in mediated self-representation. Studying their peer's mediated performances as well as source texts, students analyze their own experiences as both content providers and consumers. Social networks emerging from these mediated performances serve as proving grounds for theories of mind and machine, embodiment, multiplicity of personal and collective identities, morphing among stereotypes, hybridization, privacy issues, and finally the digital divide.

We contextualize these media experiments with weekly assignments that address non-mediated, direct, concrete human experiences. These direct experiences connect the perceived fluidity of online identities with the troubling interactions between technology, race, and gender and allow students to investigate their own ethical and political multiplicity.

Who says we ever have to stop learning?

1) Gay Talese, 24 Hour Party People and other tales about following your instinct. b/c your instinct doesn't let you down ever? does it?

And for those who still don't believe me, some advice: "Don't Be So Foolish"